Interview with Domi Sanji

- Designer, Interview

Hi Domi, can you tell us about who you are and what kind of work you're doing?

My name is Domi, I am an alumni from the first promotion of the Master’s degree in “Design and Innovation” at ISCAM. This Master was initiated by UNIDO (United Nations Industrial Development Organization) and the Norwegian Embassy which detected the need to create a pool of professional designers in Madagascar. It had a multidisciplinary design approach that I coupled with my previous background in law.

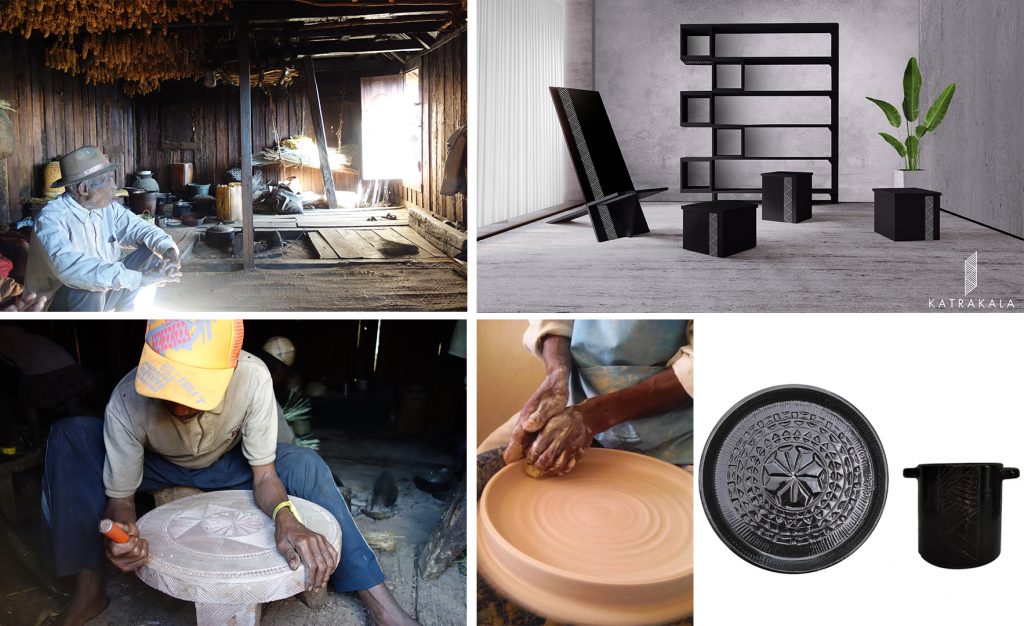

During this Master, I realised that I wanted to use design as a tool for heritage revitalisation because I believe designers have a role to play here in Mada (Madagascar) to save and renew the historical knowledge of our craftsmanship. So, I developed a hybrid methodology, including a neutral immersion phase with communities, that I experimented on my first project with the Zafimaniry community (6000 people).

Known as the forest people of Mada, they are often associated with “Zafimaniry patterns” and woodworking. My goal was to revitalize their identity in a systemic, sustainable and co-created way: to perpetuate their know-how related to wood and to inscribe their way of life into contemporaneity. The problem in Mada is that traditional craftsmanship is often associated with a doomed folklore while globalization is adopted very quickly. We are, therefore, losing a large part of our multicultural heritage.

Can you tell us more about your research and findings?

As an example, they have a very specific architecture, very similar to Japanese huts somehow: there is a flagrant minimalism and a strong codification of their interiors. The tiny huts are modular, each object has a defined place and each place has a specific function. So, I studied with them the meaning and arrangement of their huts:

– the main door is always facing west;

– in the middle, there is the fireplace;

– north of the fire, there is the guests’ place;

– northeast of the fire, there is the sleeping place; and

– south of the fire, there is the tableware.

Then, I also tried to extract and understand all their iconography. In this photo, there is the sun in the middle: it’s often the central figure and it means “sharing”. All the iconographies are wishes to the good community life: equality between spouses, prosperity for all stages of life, social cohesion, … It kind of works like an alphabet: each icon has a meaning and their assembly creates a sentence, a wish.

This is why it is important to not misuse their identity by reproducing their iconography without understanding their meanings. The question of cultural appropriation is complex because Madagascar has a mosaic of diversity. Even within Madagascar, we sometimes appropriate the identity of a region without knowing their identity and context of use. I think it’s important to develop projects in accordance with the people, to faithfully restore the iconography, and respect the meaning given by the creators of these iconographies.

What was the end-result of this project? You have developed a product line, is that right?

Exactly. To simply put it, I extracted their iconography and applied it to fast growing wood to set up a more sustainable system; the furniture have the same functionality and modularity than the huts. Even though it was a graduation project, I recently found a small factory to build 10 to 30 units where the craftmen will carve the pattern of “prosperity for all stages of life”.

It was complicated to find the right factory in Tana (Antananarivo, the capital of Madagascar) because I wanted a collection that combined the unique handwork skills from the artisan with a more industrial process. For example, I had to negotiate with manufacturers to keep a traditional “tenon and mortise” interlocking instead of screws. I also had to fight the argument of “time efficiency” with the manufacturers who wanted to supplant the artisan’s work with an automatic milling machine.

There is actually an extent to this project: I wanted to experiment this iconography on ceramic to make the Zafimaniry identity survive in the hypothesis that the wood were to disappear in their region. I tested it with two potters from Tana and I am trying to connect them with the Zafimaniry artisans so they can share their techniques. The budget for this project is still a bit low because volunteering doesn’t pay. I’ve invested my own money so far and there is no return on investment. But I love this project, so it’s fine with me, for now. This project actually allowed me to develop another project with UNESCO so it’s important to take these initiatives.

This is a message we have in common: designers are reluctant to do volunteering because we have been raised with clients abusing our charity. But on the other side, humanitarian NGOs and local associations are accomplishing a lot of work thanks to their volunteers. There is probably a balance to find. It’s interesting to see that you’re committing your time on non-paid projects and still seeing results. What are your thoughts on that matter?

I think there are projects where you must be the initiator because if no one is doing it, we will remain in a status quo that isn’t beneficial, neither for the community nor for ourselves.

I tried to position myself as best as I could on the topic of heritage so I could, subsequently, get interesting paid projects with organisations.

Alongside, I am developing other products for other clients that can generate income. I think that for product designers it’s important to create projects for different customer profiles, i.e. entry, middle, and high-end customers. It allows a designer to make a living while doing volunteer work.

So, how did this meeting with UNESCO go?

UNESCO are in a different region of Mada but they knew I was part of the first promotion of designers. They saw my project with the Zafimaniry so they decided to work with me on another heritage: the Tsingy of Bemaraha in Eastern side of Mada, to develop a line of products they could sell to tourists.

But my experience with the Zafimaniry allowed me to pinpoint an essential issue: the importance of opening these communities up. Indeed, they are landlocked people, isolated from the rest of the island: they have no TV or internet to see what is going on elsewhere; they have never seen the capital of Madagascar, which is 600km away, because that would cost them two days of travel. That’s why it was important to not make this community dependent on tourists. It was not sustainable. It was back in 2019 and the development of the pandemic, today, would have had a dramatic impact on these people if we had continued in this direction.

How did you work with UNESCO? They hired you as a consultant designer on a project-based assignment, right?

They weren’t used to working with designers because they should have hired me from the beginning of the project. Not just as a product designer developing the last aesthetical mile.

We deliberated on a Term of Reference (ToR) for a three-month project, instead of the initial six-month project, because of their limited budget.

The first month was mainly dedicated to the accumulation of data: I went to live with the community of women artisans for two weeks. It was the maximum allowed by UNESCO regarding the security of their consultants on-field. There, I collected data, iconography, materials, and I assessed the techniques of these workers in terms of basketry to eventually bring new techniques.

In the second month, I prepared a report with the artisans. We told UNESCO that we shouldn’t rush to create a product line but rather lay the foundations for something that would last.

Generally, and especially in Mada, projects are always top down decisions where the deciders try to shape the field based on their drafted expectations. UNESCO did come with a fully planned project but we offered them an alternative that made more sense and was more beneficial for the artisans. UNESCO was open to these changes. In the beginning there were some doubts probably because they didn’t expect this result from my designer’s work.

So, it was not only the development of a product line that I carried out with this community of women artisans but the establishment of a complete sustainable system:

– with the artisans, we co-created a quality charter;

– with UNESCO, we set up training courses for the artisans;

– with the government, we developed a label of the artisans’ know-how;

– we also found ways to valorise raffia (a form of palm trees used as raw material) by using a new technique, and sustain their quantity of raw material by starting a palm grove nursery.

It sounds promising, can you tell us a bit more of each one of them?

The artisans are predominantly illiterate women. Thus, to create the quality charter, it was necessary to draw inspiration from a French version, translate it into local dialects. We then explained to them the importance of it, and co-created together, little by little, this quality charter.

The end-vision was to obtain a label but we first had to raise the quality of the production and create an interesting and unique product based on their identity.

With my field research, I realised that local artisans were using a lot raffia to create braided bags and small items. But the quality of the raffia was too low, thus impacting the overall quality of the products. It’s actually a very interesting anecdote of our time. If we have low quality raffia, it’s because China is buying the premium raffia from Mada markets and only the raffia scraps that no one wants is left on the local markets.

I then suggested to the women to shift their techniques from braiding raffia to embroidering it. We had to experiment a bit and find a technique with a bucket of water so the raffia wouldn’t break but the end-result was better.

I negotiated, with UNESCO, skills development courses for ten artisans who came to Tana to see how workshops function, what the capital looks like, and to initiate a flow of openness and creativity. It’s important to see what is being done elsewhere.

Have you faced challenges related to the exodus of populations, the lack of motivation and entrepreneurship, the lack of confidence in the future or in the government? Or, on the contrary, a spirit of pride and willingness to take initiatives?

It is exactly that, it is a feeling of fatality and lack of confidence in the future. With the women artisans, it was necessary to show them the potential gains before receiving their trusts. The answers, at the beginning, were rather “we know our job, we don’t need to learn”. But, from the moment they sold their first prototypes, created during their training in Tana, at a higher price than usual, they understood that it was a real potential source of income, so their pride took a leap forward.

We asked the municipality to give these women a land in order to transform it into a palm tree nursery. The artisans didn’t know that raw material had a price. They were going into the forest: harvesting, weaving, doing basketwork, selling, and that’s it. I asked them how they were going to do once the forest wouldn’t be here anymore, and that’s how the idea of the palm grove came to be.

UNESCO is taking care of it with training in sustainable agriculture. The women also started to produce vegetables for themselves and to sell the extra to near-by hotels too.

Where do they sell their products?

They sell them at the small fairs that take place on site and in neighboring villages. But now, I think that we are ready to expand to other cities. There are bags, rugs, hats, cushion covers: products that are easy to transport because transportation can quickly become expensive in these remote areas.

What about the label, have you created it or was it already existing?

The label is in progress. And that’s where my background as a lawyer comes in: I know how to write specifications, I know the functioning of the administration, I know whom to contact and when. It makes establishing collaborative systems much faster.

For this label, I approached the Ministry of Industry and Crafts and discovered that there was a similar label than the one we wanted to create, but the application decree was somehow missing. It was actually in standby because they had an issue with funding. I was able to go up to the Ministry and ask them to provide us with an alternative solution.

In the meantime, I created a brand on behalf of these women to protect their work. The ministry assigned us an official to assist us in setting up our own label. This official will transform the quality charter made by the women into specifications; he will submit these specifications to the national Bureau of Standards, which will, then, establish the label. This is unique. Normally, the process is top down, but this time it’s the quality charter created by these craftswomen that will define the ministerial decree for the creation of the label Tsingy de Bemaraha.

What did this bring you? Do you have a specific moment that you will remember?

It brought me a reminder that social inclusion is very important. During this training in Tana, a few illiterate artisans were left aside because teachers thought they were not capable of understanding, and therefore, not capable of producing good work. But one of the illiterate person actually proved to have the best technique among the group; in a way, she was the smartest with her fingertips. One shouldn’t be excluded because they don’t correspond to our idea of intelligence: different intelligences should feed each other in an inclusive way.

Do you want to introduce us to the other projects you are working on?

There is a school project that I developed with two architects, a collaboration with the municipality of Tana, including a waste management project, and Solidarité Madagascar that I do on a voluntary basis.

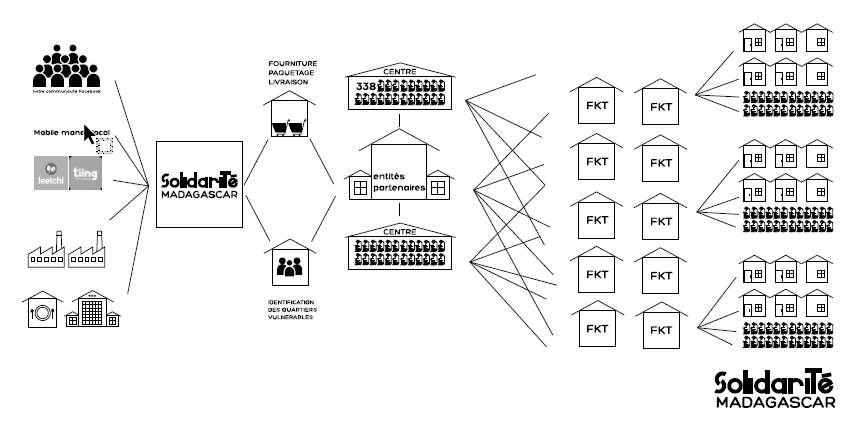

For Solidarité Madagascar, it’s a pooling donation system. The idea was developed following the announcement of the first lockdown by the Malagasy government. I gathered friends from Madagascar, Canada, and France, who are used to associative actions, and we thought about a system to help people who are living in precarious conditions such as washerwomen and cart pullers. We created a Facebook page, we condensed the ideas, we created a fundraising; companies in Tana offered us their surplus yogurt, eggs, … We naturally became an informal charity.

With our project, we first wanted to help the municipality: they had created a center for precarious people but it was welcoming only 338 people for about 1 million inhabitants. There was a real gap between the need and the response of the government. So, we went on the street to identify groups, associations, and individuals who could become partners at a neighborhood level (FKT). We tried to find areas that were not targeted by current charities to identify the precarious people in Tana. For example, while doing an interview with a fish seller in the street market, he told us “my wife and children cannot come here and help me because they don’t have masks. They’re waiting for me to come home so I can give them my mask and they can sell the rest of the fish that I couldn’t bring on my own”. Health workers, sometimes, didn’t have masks either.

As a result of this research, and thanks to donations, we decided to set up food kits made up of 1L of oil, 1kg of sugar, 1kg of legumes, a sachet of salt, and 5 kg of rice. We also distributed 2000 masks donated to us by a local shop. It’s not much, but we thought it might help. In total, we fundraised 15.000€ and distributed food to 3.037 families (families are about five people): 1.150 families in Tana, 1.000 families in the port city, and 887 in other cities.

Do you want to add some context about Madagascar?

As a reminder, Madagascar is one of the poorest countries in the world. Successive political instabilities have weakened our economy. Our action in the field has shown us that precariousness can affect many people: not only washerwomen and cart pullers but also tourist guides, drivers, waiters, staff in hotels and restaurants, etc.

Here, people prefer to die of disease rather than starve. It’s a shame to die starving. The lockdown has been very difficult to apply because people have to keep going out to find food on a daily basis.

We have a policy very inspired by the West: we are often saying that our president always speaks one day after a speech of Macron (French president). We have received millions of dollars in foreign aid but it’s not spent in the right way: the money is diluted in the administrative management. The first thing the state has done with this money was to buy 4X4.

And this is also where we gained the trust from donors: as a grassroots initiative, our donations go into food kits, period.

The government is not interested in supporting our actions. For them, the interest in supporting us would just be a short propaganda to communicate about their supposed proactiveness in supporting efficiently the people.

When the press interviewed us last year, we made it clear that we didn’t have the means of the government and that we weren’t seeking to supplant the government. The govenment is probably more frightened to see us becoming their political opponents of tomorrow but we are more interested in our fieldwork with populations. So, for now, we simply stay away from them. In the future, we would like to set up an official association to generate income through the sale of anti-waste buffets cooked by a chef from our team.

Right now, the second wave is coming and, like in many countries, the state won’t admit its weakness.

So how do you finance yourself?

Beyond my work as a Unesco consultant, I work as a freelance to develop visual identities for companies in Mada. I also finance myself through calls for artistic projects and residences. In the past, I was also doing online content management but my work as a designer takes up too much of my time now.

I am slowly transforming into an entrepreneur focusing on social actions: we are creating the non-profit association Solidarité Madagascar because the status “Entreprise Social et Solidaire”, as in France, doesn’t exist yet.

I also want to create a ceramic workshop because we have skills and artisans but very little demand. As part of Solidarité Madagascar, I discovered that graduated potters from a local high school, were all becoming taxi drivers by lack of job opportunities in the sector. So, I would like to slowly develop ceramic products.

How is the pandemic affecting you and your work? Have you perceived a change (personal or societal)? Is it slowing you down or speeding up your plans?

It has slowed down in the sense that everything is closed so I can no longer do fieldwork but it is also an opportunity for me to redefine my vision and my work, and especially how to add value to the handwork of craftsmen and women that I identified during my past projects.

Basically, you were lucky to have been proactive in the field before the lockdown; thus, being stuck at home, it allows you to capitalize on all your research and take time to reflect on them?

Yes that’s it, to take more time on side projects but also to restart a few others. Thanks to our collaboration with the municipality during the pandemic, I was also able to establish some projects:

– I suggested them to develop a project I made during my studies for better waste management.

– Their Culture Department asked me to join an advisory board to set up the city’s cultural policy.

– There is also a mobility part where they want me to redefine the bus stops of Tana, but I haven’t yet agreed because the solution is probably not in the aesthetics but elsewhere.

– We are also discussing with the Culture Department to create Tana Design Week. The goal would be to bring in designers and showcase their work; organize cultural events with the town hall; and help to create a creative and dynamic society for the town’s visibility. I always try to inject a bit of design into those projects, like the idea of a design lab that could shape the city and public places with a bottom up approach.

It’s important to always have this spirit of initiative, especially in Madagascar where everyone is waiting for everyone. Everything is still to be done here in the design sector. For example, there is no designers’ union: the government launches a visual identity contest; we do the competition; and they give a small trophy to the person who will do the work. It shouldn’t work like that. It is a public market: we must make a call for tenders. We have to support the state in implementing designers’ social rights.

We have a seen a large range of projects thanks to your proactiveness in developping though-through solutions based on design methodologies.

Thank you Domi!

Do you have more questions to ask to Domi? Join us on the Slack of Humanitarian Designers and ask him directly!

Editor’s note: article translated from French by the author of the interview.

Cédric Fettouche

Cédric Fettouche works as a design strategist for the European Commission on the New European Bauhaus Initiative.

After three years of humanitarian experience in Greece and Central Mediterranean, he founded the NGO Humanitarian Designers (HD) in 2021 to bridge the gap between the design and humanitarian sectors.

Passionate about design and societal challenges, he strives to experiment his committed vision into new sectors, and share his learnings back to the design communities. You can contact him on Linkedin or on the HD Slack.